Your Cart is Empty

Menu

Why I left academia in search of self-development

12 min read

My hindsight becomes your foresight two years after finishing my PhD and reflecting on what I've learned in Corporate R&D to help you decide on your path forward....

My thesis-writing experience felt like a microcosm test run for what an academic career would look like. Completely self-directed, filling free time with writing, very few people that can be technically helpful and few real deadlines. But in the end, I need to be successful.

It felt like this massive amorphous and ambiguous blob which I needed to shape into a body of work, but any time I pushed one section into place some other part would start spilling out and need immediate attention. I had a solid body of work but it was highly diverse with many loose ends. Although I did finish my thesis in time by the brute force method, I learned a lot about myself in the process.

I was not very self-motivated. I had trouble focusing for extended periods of time. I had mediocre organizational skills. I rarely prioritized things properly. I often took shortcuts at the expense of quality of work. I hemorrhaged time toward “writing” that was horribly inefficient resulting in little free time to be social.

I knew if I moved on to a post-doc and professor or independent researcher position, this attitude would carry over and put my long-term career in jeopardy. In contrast, the best young professors I worked with had hustle. They were getting after it doing hands-on work in the lab with their students, emailing me late at night and first thing in the morning about our collaborations and trying anything to secure more funding and grow their lab. I needed to find my own hustle.

Based on my on-site interviews, I was not going to find it in a dark and sleepy basement laboratory at a government research facility with jaded management. Instead I took a job at a mid-sized semiconductor company with a reputation (not always positive) for getting the most out of their employees. If I could cut it there, it would be because I found my hustle.

Fast forward two years.

I found my hustle. It was initially forced upon me out of necessity to meet deadlines. It’s now so ingrained that I can summon it from within myself at will. My default mode is one that hates wasting time. I try to squeeze every last minute out of each day. Best of all, I’ve found a way to turn it off like a switch when I decide that it’s time to relax. If I need to spend quality time with loved ones, I can stop the hustle (and not have anxiety) because I know I’ve accomplished so much in the time I have dedicated towards work.

Not every industry job is like this, but most have a reputation for going fast. This job, for all of its challenges, has helped me find my inner go-getter again that I felt I had lost toward the end of my PhD.

Why am I telling you this?

I know there are many others in a similar mindset (maybe you?) that are trying to make a major life decision but can’t see through to the other side. I want to be one window you can look through to get a glimpse of what to expect.

Below I detail the skills I’ve learned and developed during my time in industry. I list tips for internalizing these but many are difficult to turn on just by reading. You may have to experience industry to build these skills as lasting habits. What I don’t list are the skills I may have learned in academia. I don’t know what I don’t know. However, I do know that the skills I only learned after moving to industry will be invaluable if I return and apply them to an academic position later in my career.

Here are the skills I’ve developed since starting in industry:

Utilize every possible minute.

My thesis work was this sprawling ambiguous mass that often took several focused hours at a time to start making real progress. I would often have the attitude that “I only have 30 minutes. That’s not enough to do anything meaningful.” At my current job, I will finish a task at 10:56 a.m. before a meeting at 11:00 a.m. I use those four precious minutes. In that time, I can respond to a few emails, follow up on something I asked to be done earlier, open some files and start crunching some data, or make a plan of attack for after the meeting.

Slice a big project into small discrete tasks and goals.

(text adapted from “Thesis Writing” blog post)

The value of this skill cannot be understated and luckily can be easily learned by anyone. I half-heartedly tried this while writing my thesis but could never really make it effective.

Here are some tips that work for me: Set aside 15 minutes for planning your next 10-20 hours of work on a project. Create a large to-do list for each project (there are a lot of great Excel templates online). You can list some big milestones further out but keep the tiny details within range of tasks you could finish in the next few days. Categorize each item on 3-tier scales of “importance” and “urgency”. These two factors multiplied will show you how to best use your time.

Every morning, review your tasks and add new discrete tasks that are now within range. Add a number (1-10) to your top tasks to denote the order you’re going to work through them for this specific day. Stick to the list and avoid jumping to topics off-list that pop up. If something important and urgent pops up, add it to your list and give it a number.

Some examples for your list as if you were writing a thesis:

- Make list

- Send email to professor about feedback from Chapter 4

- Re-format figure captions from Chapter 4

- Write two paragraphs about results from experiments on October 4th-12th

- Create summary plot for above experiments

- Import and reformat data from experiments October 19th-27th

- Write rough outline for rest of Chapter 5

- Send outline of Chapter 5 to professor

- Review feedback from professor on Chapter 4

- Make list of changes in Chapter 4 based on professor’s feedback this morning

Are you the type of person that writes “Make List” on your to-do list just so you have something to cross off? Do you write down tasks you just finished just to cross them off as well?

Creating and working through a list in this much discretized detail has a lot of secondary effects. You’ll be forced to plan out your work in greater detail (and prioritize better). You’ll be more likely to use small chunks of time effectively to make progress and free up more time for yourself. Most importantly, you’ll finish your day with a sense of accomplishment and forward momentum because you got things done, instead of the feeling that you moved the needle from 23% to 24% complete after 10 hours of work.

As ridiculous as this list may sound, I’ve found it has a profound psychological effect on my motivation and momentum for the rest of the day. The key is the discipline to spend those first 15 minutes of your day planning instead of reacting to every thought or email that comes in. Try it out for one week straight and make modifications based on what works for you.

Keep track of every small detail (and every detail matters).

Everyone has been taught how to keep a solid lab notebook. But do you really record the room temperature and humidity every day? Do you keep a record of each person that weighed a powder, mixed a chemical, or ran the software to start the test? Can you track back each experiment to the individual raw materials vendors that were used and the date each raw material was received along with its certificate of compliance? I’ll take a leap of faith here and guess probably not.

You can get away with this in graduate school and often in early-stage research. But how many times have you gotten unexpected results from an experiment that later were not reproducible? You may have chalked it up to “a fluke”, right? Something went wrong but you have no way of tracking down the root cause past the obvious suspects. So, you dismiss the result and it doesn’t happen again. Problem solved?

What if that "fluke" was a breakthrough that only happened because Julia used an older bottle of nanoparticles from the other cabinet that had a 1% different stoichiometry because that vendor uses a different manufacturing method and Julia left the hot plate stirrer running an extra 13 minutes because the lunch line at Chipotle was especially long that day?

If you work in an industry that values precision, reproducibility, ppm defect rates and slim performance margins between you and the competition, you must track every possible variable. In some cases, we’ve literally had to fly to China and watch a specific operator in the factory run a new process to figure out why their result is consistently better than their coworkers.

When we figure it out, we start tracking that variable in the database. In academia this can be cumbersome and often you don’t have the proper systems set up to keep everything in a database. I’m not saying you should track Julia’s lunch break every day in an Excel sheet. I’m saying an experience in industry where these things matter will instill a stronger appreciation of small details and motivate you to find ways to track and record them for reproducibility.

Stay focused and on task for extended periods of time.

I never considered myself to be someone who had trouble focusing until I started writing my thesis. It just felt like such a big project that I didn’t know what to do next. I’d get anxious or frustrated and reach for my phone, go grab a snack or start cleaning.

I spent many hours just watching YouTube videos about motivation and productivity to hopefully find some magic bullet to fix me.

Though the videos did help a bit, the entire process was always a struggle of discipline.

Immediately when I started my job in industry (and to this day) I had zero problems focusing or staying on task. I didn’t do anything differently – it was again just a matter of necessity. If I didn’t get certain things done, I would need to stay on-site later into the evening or crack open my laptop at home after dinner. I wanted to get my work done so I could stop doing work.

It seems so simple, but in grad school I would let a 1-hour task (if focused) take 3 hours if I had 3 hours available. Conversely, in a typical day in industry you may have 10 hours to accomplish 14 hours of work. You have no choice but to stay focused. The most positive outcome of this change is that I’ve been forced to find many ways to improve my efficiency and efficacy of every minute spent working.

I keep better to-do lists, prioritize tasks more effectively, delegate more and automate whenever possible. This modus operandi became ingrained in my daily routine and I believe it would continue if I returned to academia after this experience.

Do the right work at the right time (leverage timing).

This is a skill I knew but didn’t internalize until after graduate school. When you have myriad tasks arranged neatly in front of you (see the to-do list section), you can create the luxury of choosing where and when you complete them.

Browse your top 10 tasks and decide how to best leverage the timing of completing each:

- Would completing one task make several more tasks easier or obsolete?

- Are you holding up other employees’ progress by not completing one of them?

- Which tasks must be done on-site vs. which ones can be finished at home catching the latest episode of your favorite show?

- Will anyone see or respond to the completion of a given task today, or are they out of office for a week?

- Which tasks require an uninterrupted 30 minute block of time, and which can be advanced during a time of constant distraction? Know when you’re likely to be interrupted and save the quick-hitters for then.

These categories seem obvious, but you must put in the up-front time to see your entire list and categorize each one to most effectively approach it. Below is my preferred order of attack by category:

- Tasks that enable others to make progress once complete

- Tasks that start something in motion that takes many hours or days to finish (like an experiment)

- Tasks that require long periods of uninterrupted focus

- Tasks that must be done on-site

- Tasks whose beneficiaries are out of office or in a different time zone

- Tasks that can be finished in a few minutes each on your computer but are not holding up others’ work

Know where your job ends and another persons’ begins.

One of the hardest parts of my industry job was knowing how and when to tell (not ask) a person to do something for me. In graduate research I did 90% of the work myself. The other 10% was either paid instrument time with a technician or asking someone very nicely to run an experiment for me on their instrument in another lab.

In industry, everyone should have a well-defined role. Chances are that when you’re unsure how to do something outside of your bubble it’s because it’s not really your job to do it. It’s tempting to break down those boundaries and get things done yourself for the sake of progress. But, you need to make an honest assessment of what other responsibilities you have and if those timelines will be in jeopardy if you start spending time in other roles.

What things can only you do? Make sure those get done first, then spend any free time helping others that are in support roles to you. When handing off work that you know someone else is being paid to do, don’t feel guilty if you can do it yourself. That is their job. That is why they are there. Don’t feel the need to tiptoe politely into the request each time as if they have the option to say “no”, but do always thank them for their work. If you occasionally get the response “No problem, it’s my job”, then you’re thanking them just enough!

How to send $10,000 emails.

You have to spend money to make money, as the old saying goes. R&D costs a lot of money. I was initially horrified when I realized a new substrate design I drew up needed revisions and $800 of material needed to be thrown out. In grad school that may be the cost of all the chemicals you need for a year. Then my boss told me to draw up five different versions and said, “We don’t know which one will work best, but we don’t have time to try them iteratively so order them all and we’ll make the decision from there.”

This is when I first started to truly internalize the “time is money” adage. The delay in development could cost us business worth thousands of times more than the scrap cost of that material. Later I found myself quantifying the cost of an email. These often were decisions made in less than a minute to scrap this material, ship that material, order additional testing or start a prototype production run.

Many one-line emails incurred labor and/or material costs over $10,000! Even worse, only six months into starting my new job I made a (wrong) decision that later caused us to scrap more material in a week than my annual salary.

Fired? No.

Just a “That was dumb, in hindsight” and “but that’s the cost of development.”

Remember that the lifetime of a product is expected to bring in millions of dollars. Spend the extra money up front to make a rock-solid product that will pay for itself and then some down the road. In industry, you can’t sweat the expenses of progress. Just do your best to double-check your data and have a strong case ready for every high-dollar decision you make.

When to say “that’s good enough.”

This phrase may not be in the vocabulary of a PhD student who always sees the next experiment, the next question to answer or the next article to read in the endless pursuit of knowledge. I waited almost until I graduated to publish most of my papers because the work always produced more questions than answers.

I didn’t want to publish the first book of a trilogy, I wanted to publish the entire epic.

Eventually I realized the “epic” may span a century and your PhD is meant to just be one chapter of one book. I had to find an endpoint and let the world see an imperfect work.

In industry, especially in product development R&D, you have to push out imperfect products to bring in new revenue to continue funding your endless quest for improvement. If it’s good enough to be an improvement on what customers are currently using, it’s good enough to send out to the world. This doesn’t always mean you stop development, it just means you need to wrap up the current best version. My projects currently range from 1st to 4th generation products. Each has its own challenges, and that is part of the fun! If I return to academia I will have a much better sense of when to publish and when to spin off research into a new product or company.

Final thoughts

So, what's right for you? Maybe you hate everything I said here. If so, I'm glad to have helped you make your decision! Not every industry job will be like this. But as a rule of thumb, if you're doing R&D with cutting edge technology in an industry with many competitors, it will be.

This is the type of environment in which I thrive. Where I'm challenged every day to be better, more efficient, more clever and have the resources available to solve any problem. That was not my experience in grad school or my impression from new young faculty. I needed this kick in the pants.

I hope to someday go back to academia and take some of this attitude with me for the benefit of my research and career. If you identify well with my experience then I encourage you to seek out a challenging position in industry to help bring out your full potential. Love it or hate it, you will emerge with practical knowledge and training that you may never get in a long career in academia.

Subscribe below for alerts when new blogs are published!

Do you have more questions about life outside of academia? Feel free to reach out using the email form below or DM me on Instagram @LifeAfterThePhD!

Also in Life after the PhD - Finishing grad school and what's on the other side

11 books to help get you through grad school (in 2026)

11 min read

Think you only have time to read text books in grad school? That’s what I thought too. You have more time than you think. Your future self will tell you so (trust me). The 5-15 hours and $8-$35 it will take you to read any of these books will pay itself back in time and earnings many-fold throughout your student life and in your first job offer after graduation. Invest in yourself and reap the benefits later.

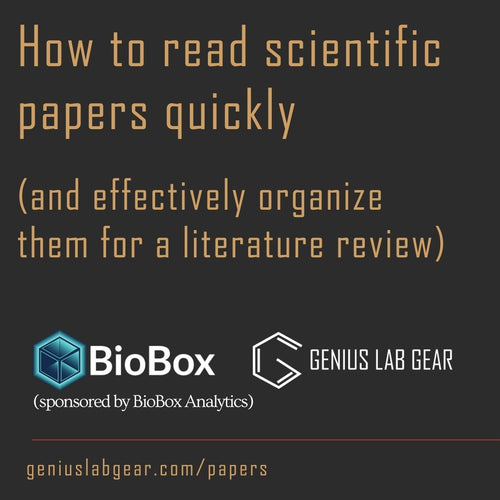

How to read scientific papers quickly (and effectively organize them for a literature review)

10 min read

It can seem like an impossible task: tediously reading dry academic research articles, following citations in never-ending circles to somehow come away with a structured literature review of the field. Two papers down and you’re already falling asleep. It’s a deeply unsettling feeling of hopelessness that I once felt as well. Here's what I did to overcome it.

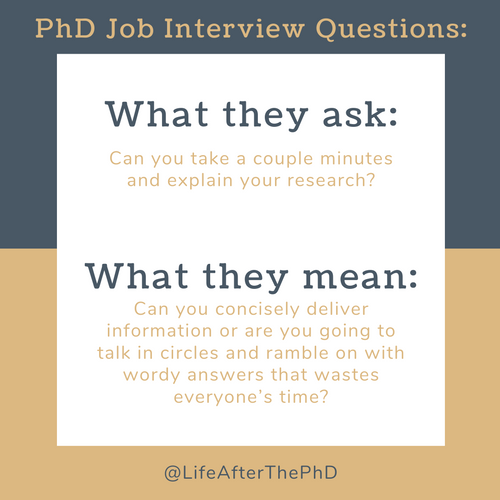

8 PhD Job Interview Questions: What They Ask vs. What They Mean

3 min read

Interview questions aren't always what they seem. Outsmart the interviewer by studying this list of common questions that are meant to answer a question that isn't directly asked.

Author

Derek Miller, Ph.D.,

Materials Scientist and founder of Genius Lab Gear

Recent Articles

- 11 books to help get you through grad school (in 2026)

- How to read scientific papers quickly (and effectively organize them for a literature review)

- 8 PhD Job Interview Questions: What They Ask vs. What They Mean

- 27 ILLEGAL Interview Questions to Know Before Your PhD Job Interview

- How I negotiated for an extra week (and a half!) of vacation at my first post-PhD research job

- How to kill it at your next conference

- Why I left academia in search of self-development

- Common pitfalls of PhD thesis writing and 17 tips to avoid them

STEM Gift Lists

Stay up to date

Drop your email to receive new product launches, subscriber-only discounts and helpful new STEM resources.

Carbon-neutral shipping on all orders

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …